* * *

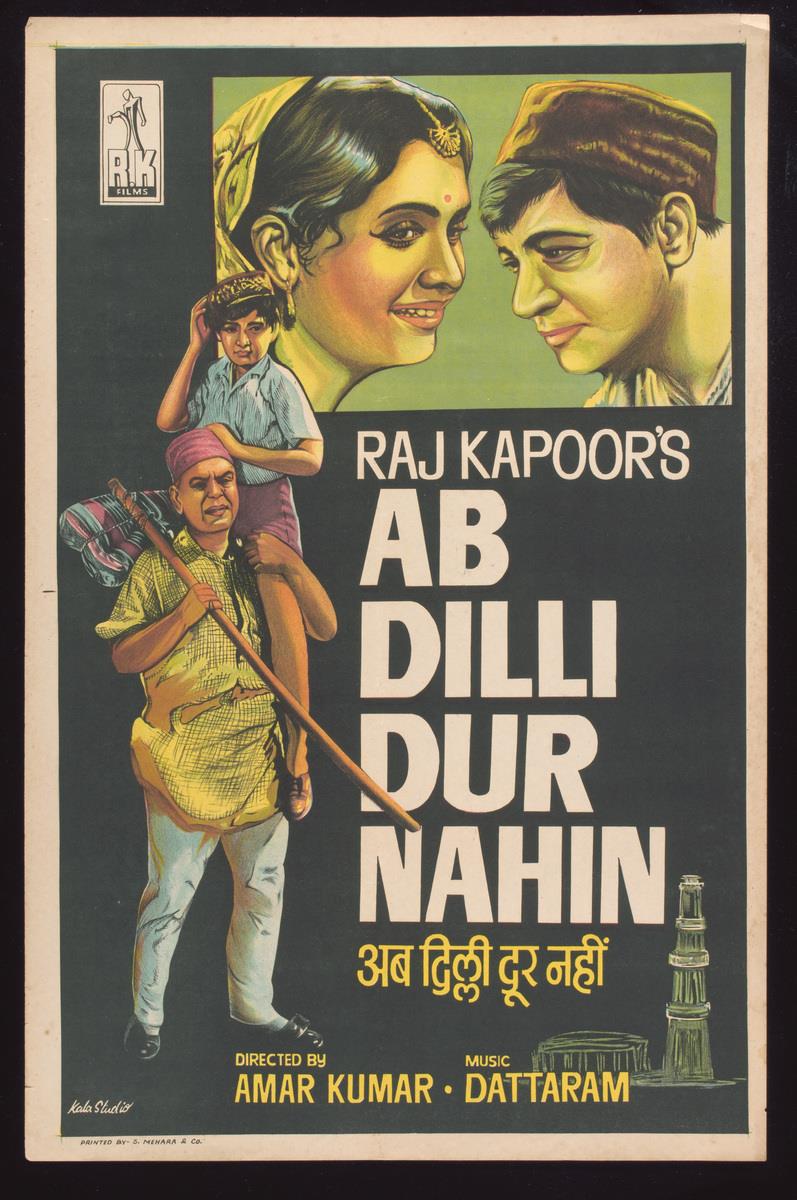

Raj Kapoor’s 1950 production, Ab Dilli Dur Nahin, carries an unmistakable Nehruvian focus that, while sometimes feeling contrived, is salvaged by Master Romi (Mohammed Salim), one of India’s first child actors. Romi, first made a name himself in the K. A. Abbas Munna in 1954, apparently the first mainstream songless Indian film. The story follows a young boy, Ratan, who travels to Delhi on a quest to meet Prime Minister Nehru so that he can attempt to seek justice for his forlorn father who has been wrongly sentenced to death.

The film opens in a village, briefly detailing the impoverishment faced by Ratan’s family. His father is burdened by debt to the local moneylender, a lecherous man with zero scruples. With his father’s wrongful imprisonment and Ratan’s departure to seek justice, the film’s excursion into the road movie territory replicates the journey narrative that was a popular feature of so many Raj Kapoor productions. Moreover, the didactic framing of societal ills established in the opening harks for an altogether Utopian future aligned with Nehru’s great plan to regenerate India as a forward facing, progressive nation.

Curiously, the extent of Amar Kumar’s directorial role is an ambiguous one, fuelling suspicions of Raj Kapoor’s possible ghost directing – a recurring accusation in Kapoor’s career whenever his name appeared as producer. We know of the ways in which neorealism filtered into popular Hindi cinema in the 1950s. While there was never a full-blown aesthetics that carried over from Italian neorealism, one can still spot the signposts or gestures. In Ab Dilli Dur Nahin when Ratan arrives in Delhi, he is befriended by a troupe of hungry and poor street kids who symbolise the other side of the Nehruvian dream that Kapoor pierces. In many ways, the street kids hark back to De Sica’s Shoeshine, a film that directly influenced another Kapoor production – Boot Polish in 1954. Here, the street kids are a family unit, with the only girl acting as the mother who scolds the boys for their juvenile antics.

Nehru does make an appearance but it is through stock news footage which is awkwardly intercut into sequences. In many ways, the crusade for justice is less mawkish when the street kids show up in the second half of the film, their camaraderie engendering a warmth and playfulness that offer a light-hearted counterpoint to the gravity of Ratan’s quest. But as Ratan comes to discover, his idealistic wish fulfilment to meet Nehru and plead his father’s innocence is full of naivety since the paragon of altruistic power that Nehru exudes has its limitations for those on the margins, pointing to the strange duality of hope and disillusionment that characterised Nehru’s vision and looking ahead to the harsh realities of post-independence India.