Bengali director Buddhadev Dasgupta’s Grihajuddha is a stark and unflinching entry in India’s third phase of Parallel Cinema, which I have titled ‘the high point’, and which often thrived on perceptive socio-political critique. Funded by the West Bengal government, this early work from Dasgupta is a tautly scripted political thriller that takes a searing look at the brutal intersection of corporate power and human cost in middle-class Kolkata. Starring Bengali stalwarts Goutam Ghose, Mamata Shankar, and Anjan Dutt, Grihajuddha opens with two brutal assassinations orchestrated by the executives of a powerful steel corporation, signalling an ominous trajectory for its characters, and, by extension, society at large.

Right from the first frame, Dasgupta establishes an atmosphere thick with impending doom. A static shot of the city, set to a relentless drumbeat, sets the tone for an escalating countdown to catastrophe. Through the eyes of Sandipan (Gautam Ghose), an idealistic journalist, the film dissects a conspiracy beginning with the death of a labour welfare officer who had dared to expose secrets about the steel company where he worked. Sandipan’s investigation unfolds against a backdrop of systematic corruption and pervasive paranoia, with Dasgupta drawing heavily on the influence of international political thrillers, particularly the moral density of Costa-Gavras’ work.

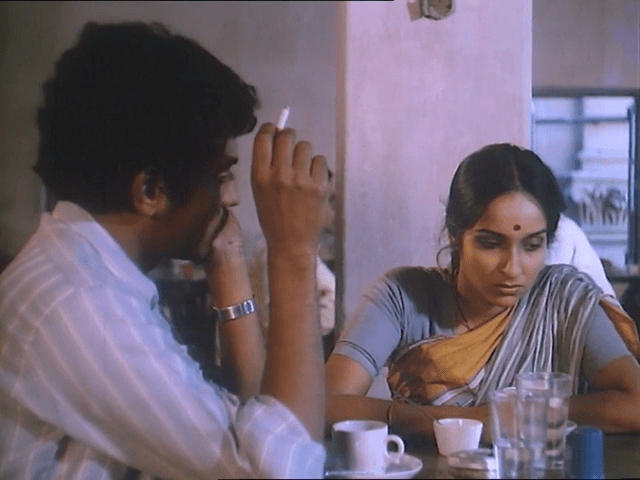

As Sandipan seeks justice, he encounters Prabir (a committed leftist union leader) and his friend Bijon (Anjan Dutt). Together, they piece together the truth behind the labour officer’s death; a murder disguised as an accident. However, Dasgupta’s vision of corporate corruption is as thorough as it is bleak. When Prabir is assassinated by a gang led by a local soccer goalkeeper in a surreal subplot, it not only disrupts his family but also sets Nirupama (Mamata Shankar), his sister, on a transformative path. With Prabir gone, Nirupama is forced into economic precarity, and her fiancé Bijon’s retreat from activism alienates her further, as his moral surrender to capitalist convenience mirrors the system’s betrayal of its workers.

Sandipan’s journey is fraught with roadblocks. His attempt to publish his findings is stymied by his editor, who pulls the story to protect the paper’s financial relationship with the steel company, a chillingly prescient reflection on media complicity and self-censorship. The consequence for Sandipan is swift and violent: his death signals the corporation’s unrelenting capacity for erasure, eliminating all those who might expose its crimes.

In the end, Grihajuddha unfolds as a layered morality tale. Nirupama’s refusal to marry Bijon in the aftermath of Sandipan’s death marks her own political awakening, a signal of resilience in a society bent on repression. Dasgupta’s film is relentless in its pacing and builds toward an atmosphere of pervasive dread. With an economy of narrative that never feels rushed, Grihajuddha indicts a society where corporate capitalism has eroded human integrity and loyalty. Dasgupta’s also hones in on the moral and personal choices confronting individuals caught in a web of exploitation, where resistance is punished and survival demands complicity. This sombre tone, underscored by restrained performances and Dasgupta’s acute grasp of the genre form, makes Grihajuddha both an essential work of Parallel Cinema and an enduringly relevant portrait of unchecked power and the human cost of compliance.