This latest piece on Aan is part of an on going series of tentative writings and research on the films of Mehboob Khan – earlier posts have focused on Roti and Aurat.

Directed and produced by Mehboob Khan, Aan is recognised as a classic of Hindi cinema. I have fond memories of Aan from my childhood, a family favourite I guess, mainly because of Dilip Kumar and the considerable, irresistible sway he had with the South Asian diaspora. Revisiting Aan after many years was a nostalgic trip down memory lane and all of those iconic, extravagant star gestures etched so fervently into my memory were resurrected in the form of Dilip Kumar’s cocky grin, Nadira’s vampish gaze (also one of the first Jewish heroines in Indian cinema), comedian Mehmood’s villainous turn and Nimmi’s vexing eyes as the enduring Mangala. The film was originally supposed to star Nargis in a leading role and a publicity ad for the film released in 1949 confirms this (see below). As I have discussed in my previous writings on Mehboob, much of his work appears to be firmly established in the canon of popular Hindi cinema, and unlike Mehboob’s lesser-known films, particularly the pre-Partition work, Aan has generated an intermittent discourse. Often under-discussed is Aan’s significance to the relationship between European and popular Hindi cinema, one that has its early commercial imperatives in the 1950s just as the South Asian diaspora in the UK and Europe was beginning to develop.

Aan was ‘the first feature film made by an Indian company to be seen in Europe’ (The Manchester Guardian, Jul 11: 1952, pg. 5), a seminal moment in the outward reach of Indian cinema. It was also the first Indian film to reach an international audience and was particularly successful in the Middle East and Africa. The distribution of Aan in Europe predates the success of Raj Kapoor’s Awaara, the first Indian film to be released in the Soviet Union in 1954. Aan had its world gala premiere at the Rialto in London on July 18, 1952, a prestigious affair, and Mehboob worked with Alexander Korda’s London Films to secure distribution for the film in the UK. In the UK and US, the film was released under the title of The Savage Princess. The presence of popular Hindi cinema is a habitual feature of the UK distribution-exhibition landscape today but Aan’s importance cannot be overstated enough since it was ‘the first Indian picture to be screened abroad on a commercial basis’ (Times of India, Aug 3: 1952, pg. 3). The commercial significance of Aan was matched by its technical innovations. Aan was one of the first full-length films to be shot in colour in India and notable in Irani’s striking twilight vistas:

‘Aan was shot in 16mm Kodachrome that followed a reversal process: a positive print was obtained straight away when shooting with this stock. A negative was made out of the positive, which then was blown up to 35mm and passes through Technicolor’s three-colour separation (making three matrices) and dyer transfer process’ (Chatterjee, 2002: 20).

The film’s international success was a critical factor in persuading the Indian film industry to embrace colour.

Aan is a fantasy adventure and in terms of its overly exotic identity recalls the feverish escapist imagery of The Arabian Nights. It is not just The Arabian Nights that are decidedly visible in the production design of Aan but the mighty spectacle that is Korda’s The Thief of Baghdad (1940), one of the most influential fantasy films of its time. I would go as far as to say the visual look of both Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948) can be seen fleetingly in the eccentric yet spectacular art design of Aan. While the film could be viewed as a pastiche of popular Hollywood film genres, Mehboob’s authorial touch is discernable in the class conflict, a recurring political theme distinguishable in many of his major works, this time emphasised in the clash between the royal Indian family and the local villagers, symbolised in the swashbuckling peasant played by Dilip Kumar. In the early 1950s, Mehboob was working at his peak, having been part of the Indian film industry since the 1930s, and later forming his own production company. Aan was an ideal film to inaugurate Indian cinema’s entry into the European film market since much of the narrative draws on recognisable fantasy adventure tropes from literature and film that would have been familiar to audiences especially outside of India. The hegemonic image of India as the exotic other was duly noted at the time: ‘I recommend it [Aan], particularly to people whose notions of the great continent revolve around Benares ware and postcards of the Taj Mahal’ (July, 18, 97: 1952) wrote Virginia Graham.

The critical reception of Aan in the UK in 1952 tells a different story to the commercial success of the film, in several respects. Writing in August 17, 1952, The Times of India, refers to the review of the film by English film critic C. A. Lejeune, in the following terms:

‘It is impossible to convey its full effect on paper, but you may get a rough idea of it by imagining a composite of ‘Robin Hood’, the ‘Arabian Nights’, ‘Il Trovatore’, ‘The Taming of the Shrew’, any Soviet picture, ‘Quo Vadis’, Douglas Fairbanks Senior, Bengal lights, the Lilian Harvey musicals, the acid colours of the latest bill posting and ‘The Perils of Pauline’.

Lejeune’s potpourri of cultural references maps an early attempt to frame popular Indian cinema as a fusion, hybrid and mix of incongruent ideas and elements. There is nothing wrong with this view. I noticed several potential film influences while watching the film. However, since Aan was the first Indian film to be released in the UK and Europe, whatever was said about the film was also in part a measure of Indian cinema as a whole. Many of the reviews I looked at fail to comprehend the film as a complete work. For instance, Lejeune’s cultural deconstruction detracts from the creative contribution of Mehboob and his highly proficient and adept cast and crew. Lejeune overlooks what is effectively a playful, creative interpretation of The Arabian Nights. Another determinant at play that certainly shaped the critical response in 1952 was to do with the running time. Aan’s UK release in 1952 was a truncated one, lasting 130 min. An hour was cut from the version that played in Europe, a substantial portion of the film. It is highly likely many of the songs would have been excised. Without songs you lose the essence of what makes popular Indian cinema so distinct. In this context, the missing hour would have certainly affected the response from critics, somewhat evident in the comments levied at the film’s supposedly erratic narrative structure.

The decision to shorten the length of the film, perhaps one taken by the distributor, underlines early and on-going anxieties to do with the apparently excessive running time of Indian films. The form and structure of popular Hindi cinema is to do with the ways in which narrative is supported by the convention of song and dance, and since Aan’s soundtrack was made up of nine (or is it fourteen?) songs, integral to the film experience and diegesis of the world being presented, songs invariably lengthen the running time but also act as a supplementary, alternative and internal commentary. Songs are also one of the major pleasures for film audiences, functioning as escapist, allegorical and narrative totems. Unfortunately, the somewhat irrelevant and illogical criticism that Indian films are too long still remains a popular default reaction from critics and film audiences. Rather than accept songs and the longer running time of Indian films as a conventional, dominant aspect of their construction, Indian films are often even today deemed to be ridiculously and excessively over long in the purview of critics outside of India. Nonetheless, given the ways in which the film audiences’ habits and tastes have shifted dramatically over the past years, the length of Indian films has become shorter but perhaps only to suit commercial inclinations.

Respectively, there wasn’t much praise from The Times of India review of Aan: ‘It is a depressing and deplorable lapse from standards and a reputation long established by one of our most distinguished film creators’ (Aug, 17: 1952). The review goes on to criticise the film for ‘its gross lack of refinement’. The Spectator review for the film by Virginia Graham is comparably expressive about the cultural debasement of popular Indian cinema, comparing Aan to the cooking of food: ‘Cooked at high pressure for a prodigiously long time, with a wicked Prince and Princess and a handsome dashing peasant and his beloved as the main ingredients, it is a layer-cake of conflicting flavours’ (July, 18, 96: 1952). I mention the food analogy since the term Masala cinema would emerge as an ignorant and contrived method of categorising popular Hindi cinema in the 1970s and 1980s. This is just one way film criticism has systemically refused to take Indian cinema seriously. Although the theory of Masala cinema has enough substance behind it now to in fact consolidate this method of categorisation as both valid and relatively intrinsic to Bollywood film discourse. I’m quite schizophrenic of the term Masala and admittedly it can be useful in some specific contexts – say for example the films of Manmohan Desai. The review continues, faltering badly: ‘That Indians make exactly the same faces as we do when they fall in love astounds me beyond measure’ (July, 18, 97: 1952), says Graham, smacks of not only a racial superiority but underlines a cultural ignorance. Although Virginia Graham does recommend the film, her review is full of hyperbole that not only overlooks the technical achievements of the production but completely fails to acknowledge the authorial contribution of Mehboob Khan, the stardom of Dilip Kumar and the lucid cinematography of Faredoon Irani.

Denis Myers damning review of the film for Picturegoer goes one step further, calling Aan ‘soul-destroying’ and mocking the director’s versatility as a desperate, superficial juxtaposition of stock narrative situations. At the time Myers opined Aan should not be released in UK cinemas because it does not meet the criteria of the quota system. However, belying the rhetoric to do with protecting indigenous British cinema from the harmful cultural effects of Indian cinema is also a belated xenophobia, which I suspect was shared by many UK film critics of the time. The overall tone struck by Myers response to Aan is a patronising one, full of mockery and contempt. Nowhere is there any attempt to comprehend the form and style of popular Hindi cinema – a good and useful starting point is to compare the internal logic of films such as Aan to the eclecticism of Parsi Theatre, a major influence on the narratological mysteries of Indian cinema. Instead, Myers works his through the film, taking the piss out of the film’s supposedly haphazard and illogical aesthetic, thematic and structural design. Mehboob directed far better films than Aan but one needs to contextualise, position and read the film in his oeuvre as a work that was a creative, stylistic experiment with colour – an attempt to evolve the technical possibilities of Indian cinema. Central here is the contribution of cinematographer Faredoon Irani to the technical advances of Hindi cinema. And since the use of colour in popular Hindi cinema has become such a vital part of the overall aesthetic and visual practice, seeing the sumptuous colours of the cinematic imaginings of popular cinema for the first time would have been a completely new and rewarding experience for film audiences. Aan was also a major leap in the career of Mehboob, whereby spectacle came to the fore, reaching its zenith in Mother India (1957). When UK film critics saw Aan in 1952, they placed a far greater emphasis on the exotic spectacle of the film as it chimed with their own orientalist assumptions of India.

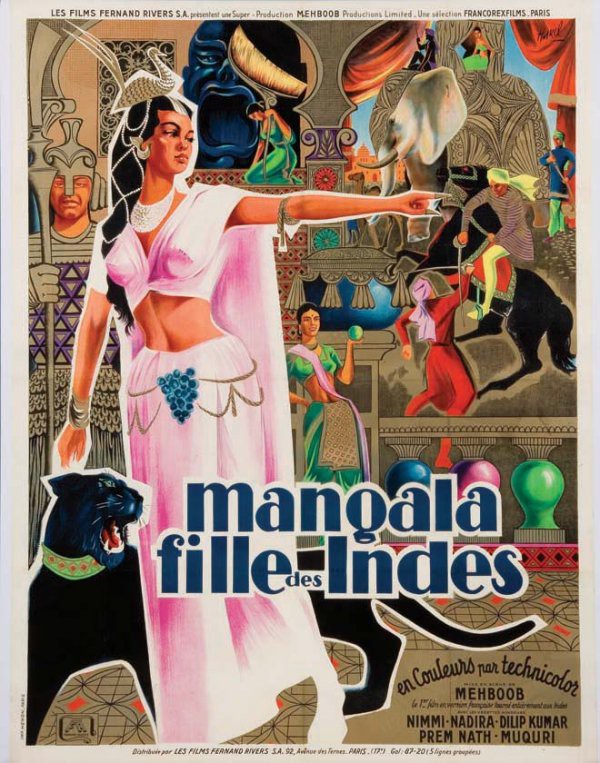

While the orientalist readings have their own contestable place, Aan like so many of Mehboob’s films demands to be revisited and viewed in alternate, wider contexts of reception. It would take Ray’s Pather Panchali, released a few years later, to completely overhaul cultural perceptions harboured by critics abroad towards Indian cinema. But this only applied to Indian art cinema. What would be useful is to try and find out what UK film audiences made of Aan; this might offer further insight and potentially challenge the critical response, one that reeked of cultural and racial snobbery. The critical response to Aan in the rest of Europe was different to that of the UK, perhaps in some respects it was more favourable, particularly in France, where the film was titled Mangala, Fille Des Indes (Mangala, the daughter of India). In France, it was the character of Mangala, played by Nimmi, which struck a chord with film audiences, as evident in the artwork to the Carlotta DVD release of the film. And it was also the French version of the film that was distributed in Europe. What remains inconclusive is the way the film was received comparatively in the rest of Europe and how widely it was distributed. Additionally, Aan is a work worth examining in relation to other films that used The Arabian Nights as a narrative source particularly the ones made by The Wadia Brothers in the 1930s and beyond. In doing so, a comparative approach would more than likely extrapolate and magnify the popularity of the fantasy adventure film, a sub genre in Indian cinema. From the perspective of Indian film history Aan is best viewed as a gateway film, the first experience of Indian cinema for an international audience. Further research is needed though to try and fully comprehend the ways in which the cinematic imaginings of Mehboob Khan shaped international perceptions about popular Hindi cinema in Europe and beyond. Perhaps a useful way forward here is to consider the ideological worth of ephemera including posters, ads, trailers, the music album, to name a few, that could offer an alternate insight into the ways in which Aan was marketed to a wider international audience.

Bibliography

AAN. 1952. Monthly Film Bulletin, 19 (216), pp. 121.

Anonymous 1952, Jun 29. World Premiere For Mehboob’s “Aan” At London On July 18. The Times of India (1861-current), 3.

OUR LONDON, F.C., 1952, Jul 11. INDIAN FEATURE FILM. The Manchester Guardian (1901-1959), 5.

GRAHAM, V., 1952. Aan. (Rialto.)-Penny Princess. (Leicester Square) (Book Review). The Spectator, 189 (6473), pp. 96.

MYERS, D., 1952. INDIA GOES HOLLYWOOD-ALMOST. Picturegoer (Archive: 1932-1960), 24 (902), pp. 8.

Anonymous 1954, Oct 16. THE EYE AND THE EAR OF MEHBOOB PRODUCTIONS. The Times of India (1861-current), 1.

CHATTERJEE, G. 2002. Mother India. BFI

Leave a comment